China is the land of a thousand car brands and a new one every month. China is the land of rapid production at an almost limitless scale. China is the land of an early electric car policy, with investments and subsidies for manufacturers and buyers. China is the land of the smart car, combining electric propulsion, 5G-connected cockpits, and self-driving features. China is the land where anyone with a novel idea and grand ambitions can become a star overnight.

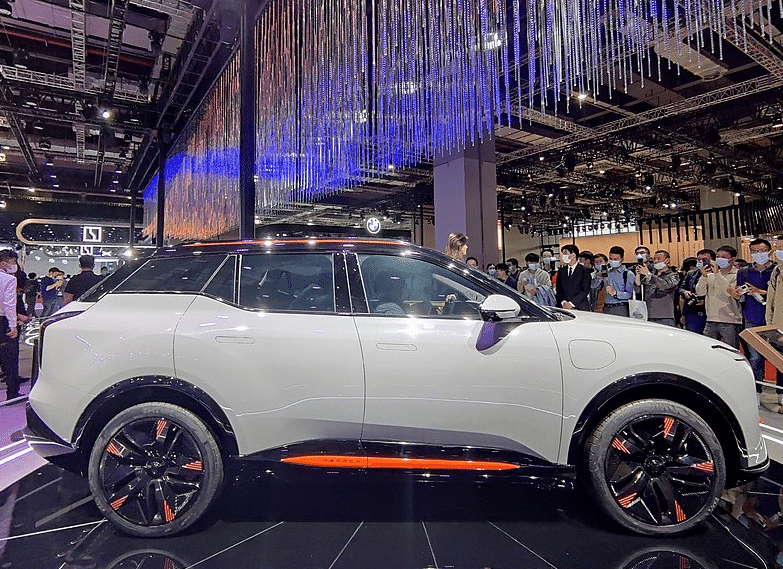

There are many people named Li among the New Energy startups (and the car industry in general) and Li Yinan wanted to become one of them. He was already a star at the age of 15, a much brighter star at 27, and now, in his early 50s, he wanted to join the club of car manufacturing rock stars like William Li, Li Xiang, and He Xiaopeng. He created his own NEV startup called Niutron and developed a rugged-looking SUV called Ziyoujia NV with all the right specs. Priced at around RMB 300.000 he entered the arena where Tesla, NIO, LI Auto, Xpeng, and a bunch of others were fighting to be the biggest star.

November 2022 was not a good month for China NEV startups. Troubling reports appeared from everywhere, but the biggest one was Niutron’s failure to launch. In a short social media message Niutron said the Ziyoujia NV would not be delivered and all 25,000 reservation holders would be reimbursed. It raised the question, is there still room for another new electric brand? Well, that’s a difficult thing to answer, but the Niutron saga certainly is an indication that times are a-changing.

This article looks back at the NEV market in China in the year 2022. The developments around Niutron form the red line, but later in the article, a wider perspective will appear. It’s a big read, but I’ll hope you’ll enjoy it.

The kid genius

To make sense of it all, let’s take a look first at Li Yinan’s spectacular resume before he wanted to become a car manufacturer. Li was born in 1970, in Changsha (Hunan province). There’s not a lot of information about his childhood, but he first made headlines at the age of 15. Li was one of only 23 teenagers admitted to Huazhong University (Wuhan, Hubei) at a very young age. The university had been scouting young IT talents nationwide and the group of 23 became known as the ‘genius kids’.

Many of the genius kids pursued academic careers, but not Li Yinan. He finished his post—graduate studies in 1993 and joined the network & IT company Huawei as a trainee. On his second day on the job, Li was promoted to engineer and within two weeks he was the deputy general manager of the R&D department. At the time, Huawei was still a young company, founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei, and it relied on reverse engineering competitors’ products to gain market share. Li however led the development of Huawei’s first self-designed series of network products, routers, and switches.

Li’s ascend to the top didn’t stop there. Two years later he was the company’s technical director and at age of 27, he was admitted to the board as Huawei’s youngest vice president. It was clear to all that Li was Ren Zhengfei’s personal apprentice. With good reason though, Li proposed, implemented, and led Huawei’s transition from wired networks to wireless GPS. That decision sent the company on a course of unprecedented growth.

The master beats the apprentice

In the late 1990s, Ren Zhengfei wanted to streamline Huawei’s business structure, outsource peripheral activities and focus on core technologies. He set up a fund to support employees starting their own businesses. In exchange for some money, these entrepreneurial employees could set up companies for outsourced Huawei activities. In a dramatic turn of events, Li Yinan decided in 2000 to benefit from this program. He resigned from Huawei, collected some funds, and started Harbor Networks, his own network IT company.

Instead of supporting Huawei, Li went up right against it. Harbor Network started operating in the same markets as Huawei itself, making the two companies direct competitors. Of course, Huawei was now an established name and Harbor was the new kid in town, so it was not a level playing field. But Harbor made inroads into the market and by 2003 Ren Zhengfei started to get worried. He started a program to directly compete with any product Harbor made and undercut it. The strategy worked and in 2006, Li was forced to sell Harbor Networks to Huawei. The master had beaten the apprentice.

It also meant Li Yinan was back in the old nest, but this time his relationship with Ren became strained very quickly. Ren first send him to the USA (to find partners and sub-contractors) and then made him head of the communications and the terminal department, to develop Li’s talents as broadly as possible. According to Ren, that is. Li himself felt tucked away in menial jobs. It’s a public secret he spend lots of his time in the R&D department, where he interfered with the development of mobile phones.

The winding road

It was clear that Li’s second stint at Huawei was not a very happy one and he resigned again in October 2008. It was the start of a job-hopping phase of his career, where he seemed unable to find the satisfaction of his earlier days. First, he went to Baidu as chief technical officer, but that lasted just a year and a half. Next up was China Mobile, where he was the CEO of Infinite Xunqi. However, mobile phones didn’t make him happy.

So in 2013, Li tried something very different. He became a partner at Jinshajiang Venture Capital (internationally known as GSR Ventures), a hedge fund that invested in many startups, among them car-hailing service Didi Chuxing. Li also started investing his own money and at least one of his investments (in Digital Horizon) made him tens of millions when the company went public.

The turnaround came in 2014 when Li met up with Hu Yilin, who was looking for an investment in his newly established company Niu Electric Technology. Hu wanted to make smart electric scooters and Li liked the idea. He invested and an Elon Musk-like scenario quickly unfolded. Li quit his job at GSR Ventures in 2015 to become the full-time CEO of Niu Electric, overshadowing the original founder. Li had found his new calling.

He spent millions on developing a fashionable electric scooter, that could be operated by using a smartphone. He targeted both the young, urban, and hip private buyer as well as the fast-growing bike-sharing market. And when to time came to conquer the market, Li Yinan was… in prison.

Lost time

While at GSR Ventures, Li received some insider information from former Huawei colleagues on a tech company called Huazhong CNC. He used his mother’s and his brother-in-law’s account to trade some shares and made a profit of about $300,000. A large number for an ordinary person, and a modest amount for Li Yinan. The Shenzhen Securities Board however picked up on the trade and Li was convicted of insider trading. In June 2015 he was incarcerated for a 30-month sentence and fined for 1 million dollars.

With Li in prison, Niu Technology was in trouble. Some investors withdrew, but others kept the company alive. In Li’s absence, Niu began to conquer the market, growing to a production of about half a million scooters a year. So, while he missed the boom in the sharing market, his company fared well in it. In December 2017, Li was released from prison. He swiftly resigned from Niu, because the company was preparing an IPO on the NASDAQ exchange and a convicted criminal as CEO does not look well. He remains the largest shareholder though, also after the IPO.

Li’s plans with electric transport were not restricted to scooters. Even before his jail time he had considered cars. In 2018 he founded Niutron New Energy Technology to get into the passenger car market. As it turns out, his two and half years in jail were a costly waste of time, because he was now well behind the curve. In 2018, many NEV startups presented their first cars and the market was about to explode.

Speed is everything

Li Yinan was aware of the fact that he missed out on timing, so all he could do was hurry up. Fast-track the development of the car, so it could launch while there was still a window of opportunity. And so Niutron decided to rely heavily on suppliers. For batteries, that’s a common strategy, but Niutron outsourced pretty much everything, from drive motors to smart cockpits. Niutron proudly proclaims to be an autonomous car manufacturer, but the self-driving system comes entirely from Horizon Robotics. Still, it enabled Li to move from founding the company to achieving production in less than four years.

Oh yes, production, the Achilles heel of many NEV startups. Li choose contract manufacturing, again in the interest of getting to the market as soon as possible. Niutron doesn’t have production qualifications, so it needs a manufacturer that has. Li assumed he had found one in Dacheng Automobile, but that’s where his ‘doing things quickly’ strategy unraveled.

Dacheng Automobile is a car factory founded in 2014 in Changzhou (Jiangsu). Initially it served in the supply chain of Zotye, making Zotye Domy vehicles. It was however not directly owned by Zotye, but by Wu Xiao, son of Wu Jianzhong, former chairman of Zotye. In 2018 Dacheng started making cars under the Dorcen brand, these were re-styled Zotye Domy cars. It also bought Jiangxi Light Vehicle, that made the JMC Qiling pickup trucks. The pickups were rebranded Dorcen as well.

In 2020 Zotye got in financial trouble and entered into bankruptcy proceedings. The collapse of the brand took a number of companies in the supply chain with it, including Dacheng. Since the end of 2020, Dacheng has not produced any vehicles and was in survival mode itself. In late 2021 a news report emerged, stating that BYD would take over the Jiangxi factory and Niutron the Changzhou factory. The BYD part was correct, but Dacheng saved the Changzhou factory with the proceeds from the BYD sale and some help from the local government. Niutron moved its offices to Changzhou nonetheless and made Dacheng its contract manufacturer.

Niutron’s market debut was supposed to take place in the spring of 2022, but due to Covid-lockdowns it was postponed. And this was a crucial mistake. By the time Niutron was ready to launch in December, the Dacheng factory had been idle for more than two years. That automatically suspended its production permit, forcing to company to re-apply and go through all the bureaucratic processes and inspections again. It left Niutron without a factory, leaving no other option then to cancel all 25,000 orders it received.

You take your foot off the pedal for a single moment and you’re left behind in China’s NEV rat race.

A market shift

For quite a few years, China’s NEV market was a startup and pioneer’s game. They determined the direction and pace. The arrival of Tesla increased the sense of urgency and the market went through a rollercoaster ride in 2020 and 2021. NIO, Xpeng and LI Auto made it to the top, Leapmotor and Neta joined them as surviving startups, just as the door began to close. Covid didn’t go away in China, supply chain disruptions kept creeping up, global inflation and a war in Ukraine began. This all shifted the market, free money disappeared and investors choose safety over opportunity. The game changed from ideas and promises to execution and branding.

In 2022, China’s legacy manufacturers finally answered in a big way. BYD and Aion showed how to increase production and we saw an influx of new, high-end legacy brands. Zeekr by Geely, Feifan (Rising Auto) and Zhiji IM by SAIC, Voyah by Dongfeng, Shenlan and Avatr by Changan, and Aito by Seres and Huawei all came on the market. Great Wall and BYD will follow soon with their high-end brands SAR and Yangwang. It’s a totally different landscape from a year ago.

And Niutron wasn’t the only one that lost out. Let’s look at two more examples.

Four years ago, WM Motors (Weltmeister) was the number two startup behind NIO, but they had an awful year in 2022. They failed to keep up with the pace of innovation and they failed to get their M7 sedan to the market. Sales were down in a record year for New Energy Vehicles. It’s so bad that WM Motors is now in survival mode. Employees are laid off and the ones that can stay, have their salary reduced by 30 or 50%. WM is behind on supplier payments and is forced to close a large number of sales outlets. As I said with Niutron, speed is everything, and WM is just too slow.

Hengchi, the brand of Evergrande Auto, threatens to become an even more high profile failure. Their first model (of a dozen announced) appeared in the MIIT announcements halfway through the year. But the troublesome position of parent company Evergrande Real Estate caused a lot of uncertainty with consumers and they voiced all kind of concerns at the MIIT website. What’s usually a trivial procedure suddenly became a burden. Hengchi was forced to provide financial security to its clients, which it did by routing all reservation money and deposits through an escrow account. This delayed the launch of the Hengchi 5 SUV by several months.

Once it was on the market and the first 100 cars were delivered to paying customers, social media began to light up. New owners began to highlight a long list of quality problems with the car, all kinds of electronic glitches, from user interface graphics not lining up on the screens to the cars not starting at all. Just when the factory had started, it stopped again. Hengchi also laid off workers and lowered wages. And it’s unclear if they’re producing vehicles. Reports say that the factory is on hold, and while Hengchi denies this, there are no sales reports or production numbers published.

Drive to survive

Do these NEV manufacturers have any chance of survival? Well, they certainly will try. Niutron reduced its staff number to the absolute minimum and is now reportedly negotiating a manufacturing deal with Shandong Guojin Automobile. Guojin is a NEV startup itself, notorious for the Citroen Picasso copy they made a few years ago. Chances for success are probably very low.

WM Motor’s founder Shen Hui invested in former German sports car maker Apollo a while ago. Apollo was revamped earlier by other Chinese investors, and it is now mostly an engineering consultancy company, but listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange. Rumors say Shen Hui will merge WM and Apollo and get a backdoor listing in Hong Kong for WM. That way he might have access to some new money again.

Hengchi is reportedly planning a novel scheme at least. Chinese media speculate that Evergrande Real Estate will try to revive the housing market by offering “buy a house, get a car for free”. That car will of course be a Hengchi model. If it turns out to be true (and it works), it will guarantee some production for Hengchi. But if it will be enough to finance their ambitious plans of another ten new models in a few years and sell millions of cars by the end of the decade, remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, the NEV game between startups and legacies is beginning to affect others as well. An Audi dealership recently put a meters high sign in the shop window, screaming “We sell EVs too”. Mercedes-Benz lowered prices of its brand new EQE and EQS models, some models even by as much as $30,000. The same goes for BMW, Chinese media report that dealers offer discounts up to €10,000 off the sticker price of i3 and i4 models. Even Tesla seems to be facing a decline in demand.

China’s economic outlook is still far from rosy. Covid-lockdowns may be a thing of the past, but now people have been getting sick in greater numbers. The USA keeps finding new protectionist policies and restrictions on trade with China. The housing problem is far from resolved. Many NEV subsidies ended in January. And so, market analysts predict that the growth of NEV sales will slow down drastically. In 2022 NEV sales grew by almost 100% to about 7 million cars, the consensus about 2023 seems to be 10 million (or a 50% increase). It will only make the battle harder.

Legacy manufacturers have shown they can answer the call of the startups. They can make equally attractive NEVs, and with the support of the country’s tech industry, almost just as advanced ones as well. Moreover, they have the advantage of scale and since this year, the advantage of access to money. The NEV startups, on the other hand, have shown great flexibility, they’re very good at communicating with their clients and they have the advantage of speed. It’s almost incredible how quickly they can bring new products to the market.

There we have the ingredients for an exciting new year. There are a couple of things to look out for. Like, who will be crushed on the NEV battlefield? Is it the foreign brands, the less-funded startups, or the Chinese legacies that don’t respond quickly enough to new trends? What does the market shift mean for new startups that have yet to launch, like BeyonCa or Xiaomi? Will they push ahead, or just give up? And maybe a lesser point, will startups that focused on the lower end of the market (Leapmotor, Neta) be able to conquer the mainstream?

Answers in a year from now, when we’re likely looking at another rearranged market full of surprises. Let’s hope Li Yinan can get his foot back on the accelerator pedal again. Just remember, when it comes to New Energy Vehicles, speed is everything!

Further reading:

Here you can find all Big read series covering the history of main Chinese automakers.

Mr. Breevoort, great informative article about failing and struggling start-ups.

But I almost missed it because of the title. After all why waste time on Niutron, just another carcass of brutal competition that had faded from the scene?

I’d rather have entitled it:

Niutron’s demise, and other faltering EV Start Ups

great to see you back!